Prologue:

What war strips from us, what it takes from cradled arms, it leaves in exchange a deep recess. What people choose to fill in that empty space depends on many factors.

I feel immense gratitude that my great-aunt chose to fill her void with art.

Because art can be dangerous. Incendiary. Irreverent. Illuminating.

As evidenced by my family’s history, art can also hope. And heal. In my family’s tale, art connects.

Part I.

My grandfather and great-aunt were born hours apart in Tallinn, Estonia on January 27 and 28, 1931. As toddlers, the local St. Olaf church discovered that they and their older sister lived in meager, impoverished conditions. Consequently, they removed the children from their single Russian mother.

To maintain their Germanization, as their father came from the prominent Baltic German von Nolcken family, the children were divided into separate German families. In 1939, Hitler and Stalin signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, ultimately dividing territories in Eastern Europe and forcing the Baltic Germans to relocate to Germany and its occupied areas, including Poland, or what the Nazis renamed WartheGau.

As a result, each sibling left Estonia separately with their respective foster families, never to return to the land that they came from.

For over 50 years, my grandfather and great-aunt lived apart, unaware of the other’s whereabouts. My grandfather, like other Baltic German families, lived at a vacant estate in Poland, then fled to Germany after the Soviet’s invasion from the east. He grew up in post-war West Germany, but as a displaced person fleeing rampant poverty, he immigrated to the US in the 1950s, gained citizenship by serving in the US military, and settled in Southern California.

My great-aunt also lived with her foster family in Poland, nearly missing the Soviet offensive. In her memoir “The Burning Train,” she recounts the harrowing month-long journey of fleeing to Germany, barely escaping the frigid winter, rampant hunger, rape from Soviet soldiers, and rogue Soviet missiles. In West Germany, she struggled with her foster family’s austere parenting and eventually ran away. After facing poverty and being held captive at a Soviet prison camp, she circuitously ventured through France, Switzerland, Colombia, even Israel, and eventually immigrated to the US in the 1970s. She settled in East Tennessee, the region where her late husband hailed from.

As a little girl, to cope with the crushing deprivation of love and affection from her foster family, my great aunt tapped into her innate talent to sketch and paint. She once told me it came to her instinctively, that her art flowed through her hands. Her father, my great-grandfather, had been a painter and that “it’s in our blood.”

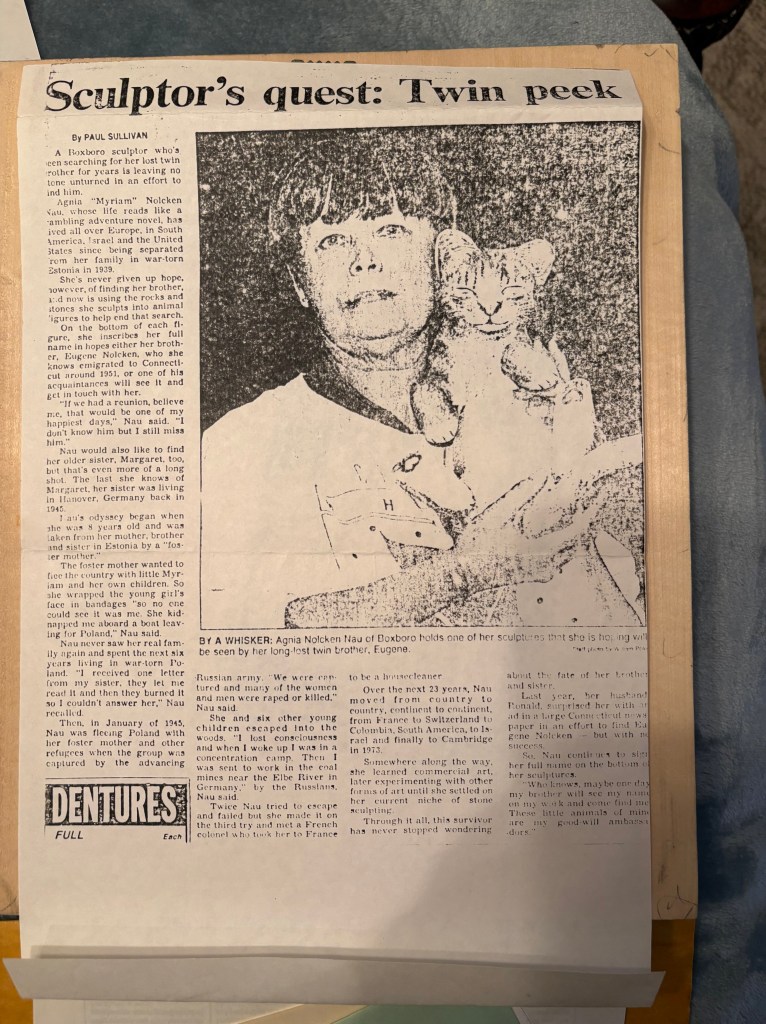

She continued her practice and opened a gallery in the mountains of Gatlinburg, Tennessee. Determined to find her twin brother, she signed all of her pieces with her maiden name Nolcken, contacted journalists to write articles about her search, and traveled to craft trade shows to spread the word.

One day in 1991, family friends of my grandfather read an article about a German woman looking for her twin brother and recognized the name. The friends had lost touch with my grandpa, but wrote a letter to my great-aunt sharing that he lives in Southern California. After combing through the phone directories, my great aunt finally found him.

After fifty years of separation, my grandfather and aunt were reunited. Because of her art.

One of the articles written about my great-aunt trying to find her twin brother.

Picture of our family meeting Aunt Myriam for the first time at the Ontario airport in Southern California, 1991.

Part II.

Family histories, of course, do not have a fixed endpoint, and one heartening reunion cannot lighten the heaviness my grandfather and great-aunt carried for their parents or their older sister. The gaping holes from their past remained, perhaps even expanded.

My grandpa had once gotten in touch with their older sister, my great-aunt Margarethe, in Germany. Unfortunately, the terrors of the war and life after impacted her mental psyche so much that she didn’t believe that my grandfather was indeed her brother. Shakespeare penned that “Parting is such sweet sorrow,” but so too are reunions with family who are in the end complete strangers.

My great-grandfather Verner-Ernst von Nolcken had, like the other Baltic Germans, relocated to Germany and lived out his years there. His role in this story and the relinquishing of his own children remain a mystery.

I traveled to Tallinn for two weeks in December 2024 to investigate him and his ex-wife, my great-grandmother. It’s been a personal challenge of mine throughout my detective work to suspend judgment on a man with such a prominent branch in my family tree. However, all of the Estonians I’ve met, including the head curator of the Museum of Occupations and Freedom, gently pressed me not to judge those that came before, that “we can only assume, but we can never truly know.”

As I think about the quiet, signature stoic temperament of my grandpa, a man who grew up without his father (a reality I too can relate with having lost my own father at eleven), I find myself turning to a quote I heard on my audio guide at the Museum of Occupations and Freedom:

“The past only tells us what choices we faced, but it doesn’t make the choices for us.”

Museum of Occupations and Freedom, Tallinn, Estonia

I’m not even sure what choices my great-grandfather faced, but from what I’ve gathered from that era, none of the choices folks faced were simple, easy, or satisfying.

Most tragically, my great-grandmother Tatjana never reunited with her children. A Red Cross worker once told my grandfather it was highly likely his mother had been deported to Siberia, but it was never confirmed.

Finding then what happened to my great-grandmother became my raison d’etre while in Estonia, but the glaring probability seemed unfavorably grim, that her fate did indeed conclude in Siberia. Several experts that I contacted shared with me the link to the Estonian Victims of Communism 1940-1991 database, which catalogues people who “suffered from communist terror.”

According to this website:

“Estonia lost every fifth person of its population of slightly over a million as a consequence of the terror imposed by the occupying regime.

Estonian Victims of Communism 1940-1991 database

A total of over 75,000 people from Estonia were murdered, imprisoned or deported.”

On the day I visited the Museum of Occupations & Freedom, I methodically read through each exhibit, hoping that a clue about my great-grandmother might emerge. However, learning more about the abject horrors of the Soviet prison camps catapulted me into a weary depression I hadn’t expected. Thinking that a family member, my own mother’s grandmother, could have perished in such a dehumanizing way made the black and white text on the different exhibits’ plaques personal. As rowdy teenagers stumbled through the exhibits’ halls, laughing and jeering at each other, I wanted to bark at them, but all I could do was sit paralyzed with watery eyes.

Determined to find her, I continued combing through the memorial website and the National Archives database, but kept finding nothing. One afternoon at the archives office in central Tallinn, a light snow descended on the city. I gazed out the window feeling frustrated; the database search engine kept spitting out “0 search results found.” Just as I was about to leave and drown my sorrows in a potent herb-infused Estonian liquor called Vana Tallinn, the archivist on shift approached me.

“I think I’ve found her…” he said calmly as he peered through his notes. “It looks like she changed her name because she remarried, but here’s some records that came up for Tatjana Nolcken-Sossi.”

I looked down at the post-it note he placed on the desk I was working at and felt a rush of adrenaline surge through me.

I immediately Google searched her full name, and there she was: she had come to life in black and white print, but not as a name marking a grave or an addition to a memorial list of those killed by the Soviets or Germans. She had placed an ad in 1965 in a local newspaper asking if anyone had information on her three children.

Instantly grateful that she hadn’t, from what I could gather, been sent to a gulag, I collected my things and rushed to the address she had listed in the ad. I wanted to walk the neighborhood she once lived in.

I wanted to freely time travel to the past.

Finding Tatjana’s full name opened so many doors to learning more about her. While I’m still trying to find where my great-grandmother was buried, I learned that she died at the age of 77 in a tiny town off Lake Peipus. Her cause of death was post-myocardial infarction scars. Translation: scarring of heart tissue. For a woman who was never reunited with her children, it seemed a poetic, tragic ending: dying from a broken heart.

The discovery of Tatjana surviving conjured mixed feelings of relief but also regret, even tears from my mom and her older sister. To know that their father’s mother had lived all that time, but was never able to be reunited with him underscores a broken bridge our family will never able to cross in this life.

Sensitive to the painful context of the Soviet era, many Estonians gently comforted me not to feel guilty over not finding Tatjana sooner. The Soviet era was mired in unimaginable oppression and brutality. Searching for Tatjana during that time would have been dangerous.

Newspaper ad my great-grandmother sent trying to track her missing children, nearly 30 years after they were taken from her.

Part III.

What war strips from us, it leaves a deep recess. I can’t help but wonder if that void passes on generationally, that the pain felt by my grandfather and great aunt lives on in my own marrow.

Otherwise, how do I explain the deep connection I feel with Estonia? How it feels like a homecoming I never knew I needed.

It’s as if I’ve been running through a dark forest in the frosty night, then spotted the warm glow of a cabin, pulled open the front door, felt the greeting of the fireplace’s heat on my bare skin, and I know I’ve arrived. I’ve made it home.

I can’t be sure whether these feelings are just my own romanticization of my time in Tallinn and Tartu, or maybe it’s closing an important chapter in our family’s history, but as someone constantly pining for evergreen forests, fresh air, and a connection to something outside of the US, I’d like to think this is my family’s past singing in my genes.

To conclude, I’ll share a poem my great-aunt wrote when my grandfather passed away in 2011. Even then, she filled her void with art, capturing how my grandfather, even up until his last breath, also longed for home.

“My Brother”

by Myriam Nau (Agnia von Nolcken)

Death knocked at my heart, the time of sorrow had come.

My brother’s plea to take him, I can’t forget.

His anger grew, he cried out loud, “Please take me home.”

Behind his despair stood death, a hideous face I met.

Dawn broke and my brother whispered,

“Please take me home.”

I took his hand, once so full of life, and cried,

“I can’t take you home.”

He lay quiet, not here anymore, yet breathing the same air I breathed.

I kissed him on his forehead for the last time.

His face was at peace; he was at home.

SPECIAL THANKS & Acknowledgements:

Researching my family’s history could not have been possible without the amazing, generous, patient people I met during my time in Estonia (in no order):

1. the staff at the National Archive Madara Reading Room / Rahvusarhiivi Madara uurimissaal. Every time I ran into a dead end, 20 minutes later, a staff would approach me with a new clue that continued to open doors. Their determined intentionality and thoughtfulness is a gift I’m not sure how to reciprocate except expressing repeatedly many thanks.

2. the staff at the Tallinn City Archives / Tallinna Linnaarhiiv (see above with same compliments)

3. the staff at the National Archives of Estonia in Tartu (see above ^)

4. Liisi Rannast-Kask, Head of Collections at Vabamu

5. Wendy, tour guide extraordinaire from the “Discover the Hidden Magic of Tallinn” tour who helped paint a clear context of Tallinn’s history so that I could connect the dots that related to my family.

6. Jónas Þór Guðmundsson, local historian with infinite knowledge of Estonian history and tour guide of “Communist Stories of Tallinn Walking Tour.” His generosity helped me find the neighborhood my great-grandmother once resided in Tallinn.

7. Gustaf H., affiliate of The Monk’s Bunk Hostel who shared with me information about Estonia’s impressive archives database and encouraged me to keep looking.

8. Laura Lillepalu-Scott, Manager of Alatskivi Loss, whose magnetism, lively storytelling, and generous enthusiasm for Estonian history leap at you like a warm hug.

9. Olga Kistler-Ritso, an Estonian refugee whose generous donation made it possible to create the Museum of Occupations and Freedom / Vabamu. This incredible museum, which powerfully holds nuances of a time laden with heartache and hope, preserves Estonia’s historical memory and amplifies the voices of those impacted by the Nazi and Soviet regimes.

10. Hannes at Sir Autorent who kindly helped me rent a car last minute so I could drive to Alatskivi, Kasepää (the birth town of my great-grandmother), and Tartu.

11. All of the staff at The Monk’s Bunk who helped answer my logistical questions

12. To the gals that came through room 11 of The Monk’s Bunk: your humor, kindness, and love for adventure embody the truest treasures of the roads we all travel

13. To my mom, my aunt Heidi, and my sister: our strength comes from a long line of survivors, but I’m so grateful we get to live in a time where we can do more than just survive; we can thrive.

14. To my grandfather, your language of quiet stoicism I now humbly understand. Sometimes silence speaks more poignantly than words.

15. To my great-aunt Myriam: bless your hands for what you’ve created. It’s more than you could ever know.

Leave a comment